By Nicola McCullough, Alex Culvin, Gordon Fletcher & Alex Fenton

As we consume less things, we seek out more experiences. There is a growing trend for people to spend money on experiences not things. This movement away from the pivotal importance of purchasing and owning things can be described as the rise of the Experience Economy. Only in the Experience Economy could ownership of an item be assessed solely on the basis of whether it ‘sparks joy’ and then have an entire Netflix series (Tidying Up) based around repeatedly asking this one question. However, the makings of the Experience Economy can be identified in much earlier academic work. For example, Future Shock (Toffler and Toffler, 1970) discusses,

how the economy is being created geared to the provision of psychic gratification, that a process of “psychologization” finds place and humans will strive for a better quality of life.

The critical theory perspective offered by Guy DeBord (Society of the Spectacle, 1967) also opens with the observation that,

In societies where modern conditions of production prevail, all of life presents itself as an immense accumulation of spectacles.

The democratisation of air travel with cut-price airline operators, the freewheeling second Summer of Love, the rise of diverse and niche music festivals, boutique hotels, specialist retailers who are a destination, new formats for old sports, including 20/20 cricket and 7-a-side rugby, as well as new participatory sport events such as ‘tough mudders‘ have built ‘psychic gratification’ and ‘spectacles’ into increasingly sophisticated and compelling moments that define the current Experience Economy. These many examples reveal that what constitutes the Experience Economy is dynamic, fluid and forward facing in ways that heavily shape our entire economy.

As business, society, economics and politics shift so does the Experience Economy.

Young people (particularly millennials) are driving this wide-ranging change in perspective. By placing greater emphasis on the value of being involved in specific experiences, rather than obtaining material possessions, the priorities of businesses must also continuously adapt. Investing in the opportunity to create experiences will be critical to any post-pandemic economic recovery and will increasingly shape what ‘we’ do. At Salford Business School, we aim to give our students the best opportunity to excel in the shifting Experience Economy.

Young people & digital identity

Millennials and Generation Z embrace digital media devices as pivotal tools in their work, academic and social lives. This broad engagement with devices that can be both receiver and sender of media also reflects the ‘demotic turn’, where everyone sits on both sides of the broadcast media supply chain as consumer and producer. This relationship has a long history, but it sums up the connection between trends in the Experience Economy and young people.

New figures show we are continuing to spend less money on buying things, and more on doing things – and telling the world about it online afterwards, of course. From theatres to pubs to shops, businesses are scrambling to adapt to this shift – The Guardian

Many young people, and in particular those who seek to influence others, are spending increasing amounts of time and money carefully choosing locations in order to curate a fabulous and substantial Instagram and TikTok social media followings. These professional profiles often focus on lifestyle experiences, fashion, socialising and travel. Cameras and social media merge the Experience Economy with the demotic turn. This means that having an experience is not confined to being only a personal one, but an important part of creating an online identity. Having an experience is not complete for many unless they also share it online with friends, family and followers.

Transforming the consumer experience

The Experience Economy transforms consumer experience. The personalisation of all we do, see and interact with, and how this elevates our senses presents new challenges to service sector businesses. And there are many ways that this change is being experienced.

The first is memorability. The heightened emotions during the current crisis make this a period where lasting memories are going to be made. People will recall brands that were authentic in their care and humanity and found ways to adapt their experiences to customers’ changing needs.

Transformation is indeed another. This will go beyond the current focus on personalisation, to brands having a genuine link to people’s lives, aspirations and dreams – many of which will be different after COVID-19. People will expect brands to adapt, understand what is now important, and provide experiences that have a lasting and positive impact on their lives.

And last, but not least, Sustainability. The pandemic has reminded the whole world that there is more to life than material possessions and has demonstrated what is possible when we act collectively.” – Dr Susanne O’Gorman

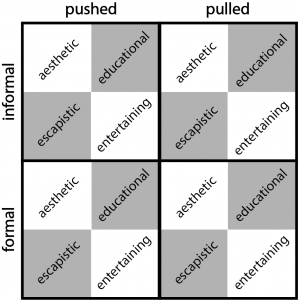

Pine and Gilmore defined four different types of experiences: Escapist, Entertaining, Educational and Aesthetic. People can actively seek out experiences (such as going to a concert or a football match) or people can passively – even unintentionally – receive an experience (such as an unsuspected event outside your normal daily routine). We can pull experiences to ourselves or they can be pushed to us.

Further categoration of the variety of experiences is possible between formal economic activities that aim to deliver experiences to people who pay directly or indirectly for them (Sundbo and Sorenson, 2013) in contrast to informal activities that are an unexpected side-effect or consequence of other economic activities. This range of distinction can be summarised as the difference in the experience of a taxi driver who memorably entertains you by singing your favourite songs in contrast to them then delivering you to a restaurant where you experience a once-in-a-lifetime sampling menu with your family.

According to Pine and Gilmore in 1999, experiences are “events that engage the individual in a personal way.” Experiences are set on a stage that caters to the individual consumer through a specific combination of goods and services in ways that have lasting impact and memorability. They are intangible and bespoke on every level.

Opportunities for the Experience Economy

At Salford Business School, we are ‘doing’ the Experience Economy with the development of modules that engage our students in industry. Experiencing the world of work during a course of study is the type of informal activity mentioned above. It is vital that students observe and engage with such concepts to ensure the applied nature of their understanding is capitalised upon.

The Experience Economy crosses, and even ignores, disciplinary boundaries. It is part of, and relevant to, sport, retailing, fashion, cultural and creative industries, marketing, any digital ‘user’ experience, operations management, events management and production, sustainability, tourism and all aspects of arts and media.

As such a disrepector of previous categories that are more suited to the discussion of goods or services, there are opportunities for the most ambitious to shape themselves as ‘experience entrepreneurs’ or ‘experience innovators’ by taking on the assumptions built into roles and disciplines that were shaped during different times and with different types of economic priorities. The Experience Economy is a hybrid of what has come before but it is also a reflection of how we want to ‘do’ now. Moving to a post Covid world, the Experience Economy will become the default to many across the service sector – those working, consuming or simply engaging with it.

Contact us for more information and to discuss ways to collaborate further to explore these topics.